Newborn screening for rare diseases caught up in red tape

Newborn screening for rare diseases caught up in red tape

The call to test newborns for rare, but treatable diseases is growing. A FOX6 investigation finds the bureaucratic marathon proposed rules must endure could result in deadly delays.

MILLADORE, Wis. - The call to test newborns for rare but treatable diseases is growing. However, the process for approving those diseases is long and cumbersome. A FOX6 investigation finds the bureaucratic marathon proposed rules must endure could result in deadly delays.

By the time Gwendolyn Clubb was born in August 2017, her parents already had five other seemingly healthy children, so the big family from the tiny Wisconsin village of Milladore was not prepared for the call they received about a week after she was born.

"And we're like, ‘You must have the wrong person,’" said Stephanie Clubb about the day she and her husband learned Gwen had tested positive for Pompe disease.

"I don’t know what the heck that is," said her husband, Michael Clubb. "You Google it and I couldn’t make it past the first paragraph."

Stephanie and Michael Clubb had never heard of Pompe disease until their daughter, Gwen, was diagnosed shortly after she was born in August 2017.

Pompe is a genetic disorder that robs cells of the ability to recycle complex sugars. The resulting build-up of waste causes muscle weakness, labored breathing and eventually, heart failure.

"We were told to go home and love our baby," Stephanie Clubb said.

For the most severely affected infants, Pompe can be a death sentence.

"It was devastating to think she wasn’t going to make it until 2," Gwen's mother said, fighting back tears. "Devastating."

In summer 2017, the state of Wisconsin started testing all newborns for Pompe as part of a federally-funded pilot study. Over a period of nearly two years, they screened 108,862 newborns. Thirteen (13) tested positive. That's one out of every 8,374 babies born in Wisconsin.

Fortunately for the Clubbs, Gwen has a less severe form of Pompe that may not show symptoms for years.

"We’re so blessed to be able to monitor her," Stephanie Clubb said.

Because Gwen was tested at birth, her parents know what symptoms to look out for so they can immediately start enzyme replacement therapy.

"A treatment to have them be healthy as long as possible," Stephanie Clubb said.

FREE DOWNLOAD: Get breaking news alerts in the FOX6 News app for iOS or Android

Not every child with Pompe in Wisconsin has been so lucky.

Atlas Faucher was born in Oshkosh in 2016 before the state's Pompe study began. At 3 months old, his heart began to fail. He was rushed to Children's Wisconsin, where doctors eventually discovered the cause was Pompe disease.

Atlas Faucher was born in 2016, before Wisconsin's Pompe pilot study began.

"The fact that he had to wait to be so symptomatic did have a detrimental effect on him," said his mother, Genevieve Faucher.

Atlas is in a wheelchair, and while he is able to speak, his words are slurred and not always easy to understand. A team of nurses and physical therapists assist his parents with his care. Genevieve is grateful for the enzyme treatments that have slowed or halted the progression of the disease but fully aware newborn screening could have made his life much easier.

"Ultimately, damage that’s done is damage that’s done. There’s no reversing that," she said.

"His quality of life is totally the opposite," Michael Clubb said while watching his daughter climb and play on a Stevens Point playground.

"Early identification makes a difference," said Dr. Mei Baker, co-director of the Newborn Screening Laboratory at the University of Wisconsin.

Wisconsin's Newborn Screening Laboratory tests blood cards collected from more than 60,000 newborns every year for more than 50 disorders.

The NSL takes blood cards collected from newborns at the hospital through a heel-prick blood test and screens them for nearly 50 disorders from cystic fibrosis to sickle cell anemia.

"I think the beauty of newborn screening is really that prevention is emphasized," said Dr. Baker. "This is the future of medicine… to prevent disease."

Dr. Baker calls Pompe the "perfect example" of the type of disorder the state should be testing for.

There's just one problem.

The Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene stopped testing for Pompe when the pilot study ended in 2019.

"OK, we need to do something about it," Stephanie Clubb said.

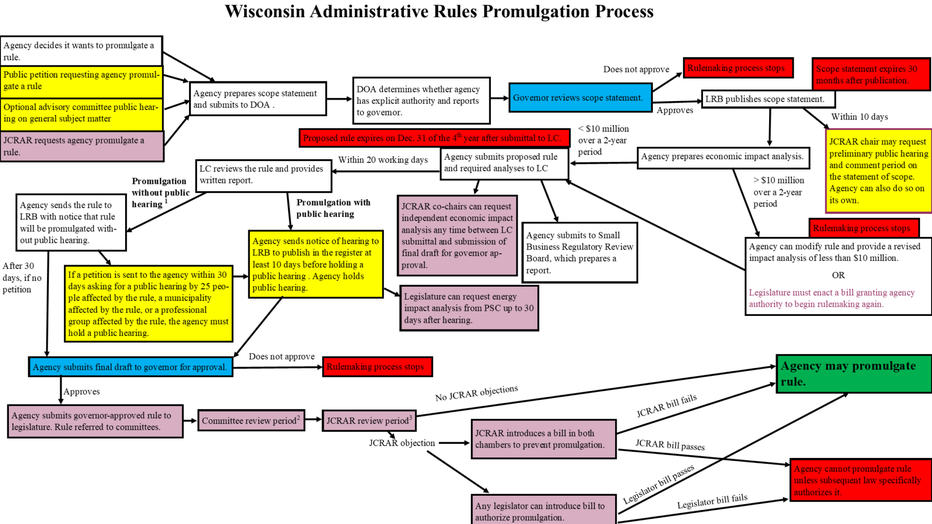

So the Clubbs went from small-town parents to statewide advocates. They nominated Pompe for permanent inclusion in the newborn screening program. They secured the support of then-DHS Secretary-designee Andrea Palm, as well as Governor Tony Evers. Two years later, their proposal is still winding its way through a long and convoluted rule-making process.

"We’re kind of stuck on the back burner," Clubb said.

A life-saving test is buried in red tape.

"We're like, ‘OK, when is this going to come to help other families?’" Stephanie Clubb said.

"This process was definitely eye-opening," Faucher said.

State Senator Patrick Testin said he tried to follow that same process for another genetic disorder known as Krabbe disease.

"We’ve tried going through the normal process. That process has failed," he said.

Like Pompe, Krabbe is fatal in its most severe form if not detected early. According to Dr. Baker, the two diseases are so similar, if they start testing for one, they could include the other for free.

"Adding one disorder [to the other] would not have an additional cost," she said.

Pompe testing is estimated to cost $671,000 per year, or roughly $11 per newborn, but Dr. Baker said adding Krabbe testing to that would cost nothing.

"So basically, we’re getting a two-for-one deal here," said Testin.

In June, the Stevens Point Republican introduced legislation that would tie Krabbe and Pompe testing together.

"That can piggyback onto what we’re doing," said Michael Clubb.

"Power in numbers, absolutely," said Stephanie Clubb.

The Clubbs now have seven children, and because of Gwen's diagnosis, they decided to test them all for Pompe. Three came back positive.

"Seven beautiful kids. What are the chances?" said Stephanie Clubb.

She said newborn screening is no longer about them.

"It's so much bigger than us and our family," she said.

After all, when lives are at stake, there's no time for red tape.

The Wisconsin Department of Health Services declined an on-camera interview for this story. Instead, the department provided written answers to specific questions posed by the FOX6 Investigators.

Chuck Warzecha with the DHS Division of Public Health said, "Every effort is being made to begin universal statewide screening for Pompe Disease as soon as possible to reduce the risk of a child with Pompe Disease being born in Wisconsin prior to implementation of screening."

However, Warzecha could not estimate how long that will take.

As for Krabbe disease, DHS said it still needs more information. A public hearing on Senator Testin's amendment attempting to link Pompe and Krabbe screening together is scheduled for Thursday, July 28, at 9 a.m. at the Capitol.