Kaszube descendants reflect on life at Jones Island amid effort to revitalize area surrounding it

Kaszube descendants reflect on life at Jones Island amid effort to revitalize area surrounding it

Kaszube descendants reflect on life at Jones Island amid effort to revitalize area surrounding it

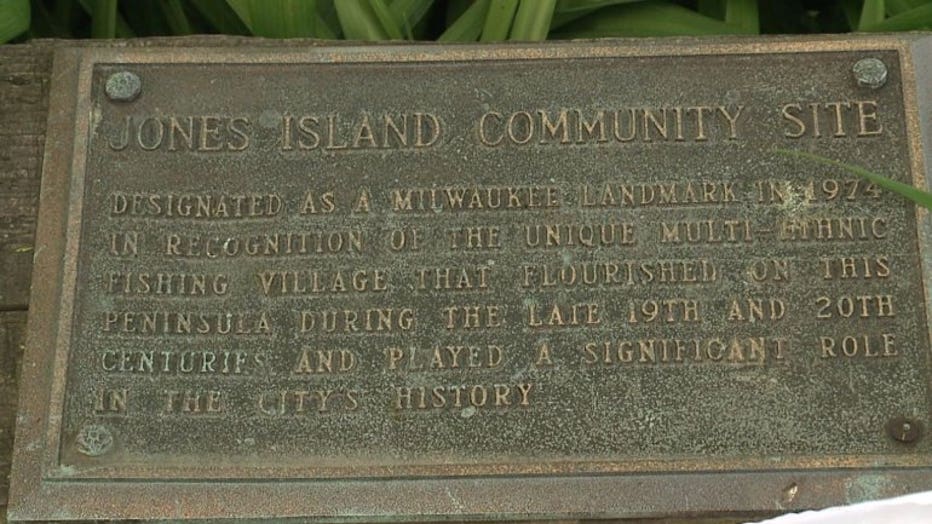

MILWAUKEE -- There is a hidden history tucked along the banks of Lake Michigan, in the shadows of shiny high-rises and big ships, in the middle of Milwaukee industry.

“Jones Island is everything to me,” Linda Gatton said.

It’s a place known to many in the Cream City as the home of Milwaukee’s sewage plant, but for Gatton and her friend Barbara Suter, it’s their heritage.

“Growing up, most kids had bedtime stories read out of books. My father would sit on the edge of my bed and tell me about life on Jones Island,” Gatton said. “Those were my bedtime stories.”

Barbara Suter and Linda Gatton

Gatton and Suter are descendants of Milwaukee’s lost fishing community.

“They lived, and worked, and played here, basically,” Suter said.

Gatton’s great-grandfather was among the first to move to Jones Island in 1869. He was part of the Kaszube people who emigrated from the Baltic region of Europe to Milwaukee. Many made a living by fishing.

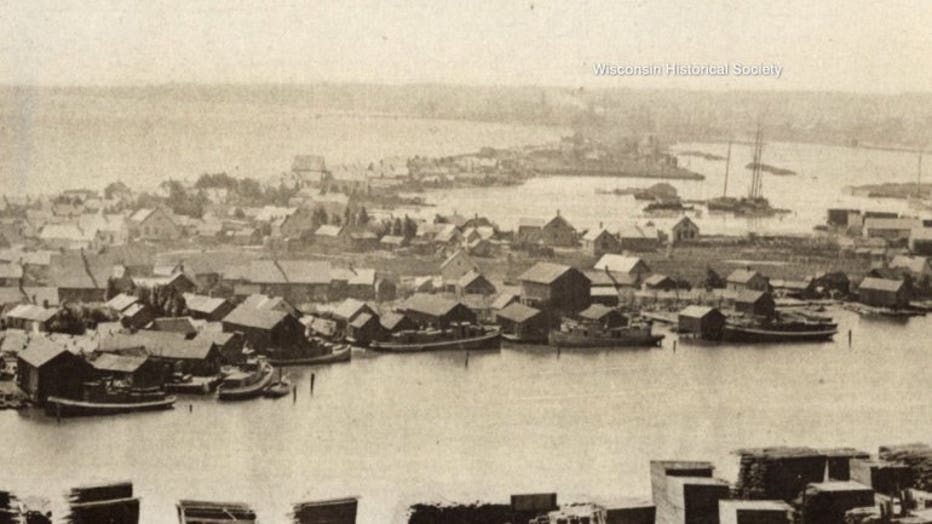

At one point, more than 1,600 people occupied Jones Island. The area took its name from James Monroe Jones, who attempted to open a shipyard there in the 1850s. His shipyard didn’t last, but his name did. His efforts were the first of many that would turn a small, marshy place into a vibrant peninsula full of a unique culture.

“This was about the closest thing Wisconsin's come to having a genuine urban village,” said John Gurda, Milwaukee historian.

The Kaszube lived on the land without the benefit of title, occupying the area for more than 60 years.

“They were very much kind of an anachronism," said Gurda. “They were something from the past as the city began to change around them.”

In the 1920s, change came knocking at the doors of the Kaszube. The vast majority of people were evicted as the sewage plant opened. The City of Milwaukee condemned the land and paid the islanders to move. The last resident left in 1943.

“To some degree, it's sad when you think about people who had that way of life for generations, no longer can live it,” said Gurda. “At the same time, it's pretty hard to argue that they were not behind the times, and there was interest, even on their part, to kind of move into the modern world.”

No one lives on Jones Island anymore, but the traditions are rich in its descendants. Gatton and Suter volunteer at their church fish fry. Jones Islanders may have been the first in Milwaukee to popularize the Friday night favorite.

“I guess it's in your blood to love fish,” Suter said.

While the descendants are keeping Jones Island’s memories alive today, Dan Adams,has his eye on its future. Adams is the planning director for Harbor District, Inc. He’s part of an effort to revitalize Milwaukee’s Harbor District.

“It will be a very different place in a few years’ time,” Adams said.

Though Jones Island will remain untouched, the area around it could see new housing, jobs, and recreation.

“We're seeing a lot happen in the near future, but some things could take five, 10, 15 years out,” Adams said.

Life may once again return to the area. For Gatton and Suter, it is bittersweet.

“I think this little patch of grass and these trees, hopefully, will serve as reminder to people that this was, at one time, a very thriving community, with people who loved the lake and loved the land that they were living on,” Gatton said.