Doctors, patients: Efforts to block opioid addiction are also blocking treatment

Doctors, patients: Efforts to block opioid addiction are also blocking treatment

Doctors, patients: Efforts to block opioid addiction are also blocking treatment

MILWAUKEE — Just walking up to a pharmacy window is enough to send Tina Kasten's brain into overdrive.

"You freak out," Kasten said, using words like "anxiety" and "stress" to describe how she feels when she tries to pick up her prescription.

Kasten, who lives in Manitowoc, takes Suboxone as part of her treatment for heroin addiction. She said she has experienced delays in filling her prescription a half-dozen times over the last year.

Thirteen other patients described similar experiences in Wisconsin to the FOX6 Investigators. They did not want to be identified, citing the stigma of addiction.

Doctors, counselors, and pharmacists in Wisconsin say efforts to fight opioid addiction are inadvertently making it difficult to get addiction treatment.

The 'devil and the angel'

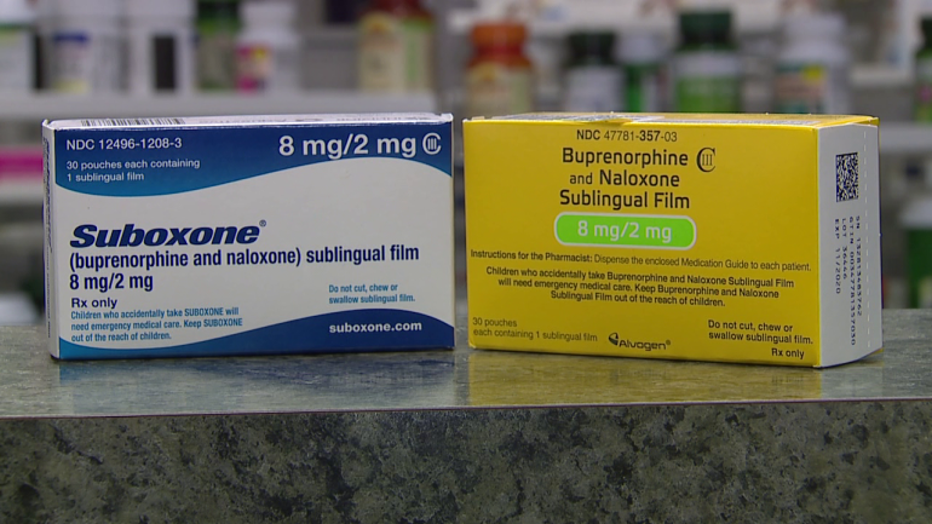

Suboxone is a medication that contains buprenorphine and naloxone. It is used in combination with counseling and behavioral therapy to treat opioid addiction.

Drugs like Suboxone work by partially acting like an opioid and binding to the same receptors in the brain.

"That's what allows it to be so useful in addiction treatment," Dr. Selahattin Kurter said. Kurter is the executive director of West Grove Clinic, which provides mental health and addiction treatment.

" doesn't give you the euphoria associated with opiates," Kurter continued. "But it protects you from the cravings and withdrawals."

Kurter is Tina Kasten's doctor. Kasten credits the combination of Suboxone and therapy for her addiction recovery.

"I didn't have the cravings all the time," Kasten said. "It wasn't constantly on my mind like, 'OK, am I going to use? Am I not? Am I going to use? Don't do it. Oh, but you should.' It's like the devil and the angel and Suboxone tells them to be quiet and go home."

"I put the work in to deal with the emotions and deal with everything that led me to be a drug addict," Kasten added. "The Suboxone didn’t do that work. I did. But the Suboxone helped."

But there is a danger patients could abuse Suboxone or illegally sell it for its opioid-like qualities; it is a Schedule III drug, which the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration says could lead to "moderate or low physical dependence or high psychological dependence" if abused.

"It can be used to help somebody get rid of the addiction to opiates, it itself can be addictive," Dr. Hashim Zaibak, pharmacist and CEO of Hayat Pharmacy said. "So the pharmacist has to balance between the risk and benefits of Suboxone and that can be a challenge."

Red flags

As the opioid crisis spread, there was a push for Medicated-Assisted Treatment (MAT): The combination of drugs like Suboxone and therapy.

The Director of Wisconsin's Prescription Drug Monitoring Program says the state has seen a 66% increase in Suboxone dispensations since 2016. A federal rule change expanded the number of patients that providers can treat with MAT, and gave more providers the ability to use MAT.

The Department of Health Services has also been facilitating training to give health providers the ability to prescribe buprenorphine, the active ingredient in Suboxone. Data from the Department of Health Services says one year ago, there were 850 available buprenorphine prescribers in Wisconsin; now, there are 1,117.

While these measures made it easier to have initial access to drugs like Suboxone, other measures made it more difficult to take the medication home.

To curb opioid abuse, pharmacists are guided to turn patients away if there are too many "red flags." Examples include cash payments, returning too frequently for refills, signs of doctor shopping, family members receiving prescriptions from the same prescriber, and driving long distances to fill prescriptions

The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration says it is a felony offense for a pharmacist to deliberately ignore a questionable prescription when there is reason to believe it was not issued for a legitimate medical purpose.

Dr. Kurter says these measures are important to prevent opioid abuse, but also says it's easy to forget that one patient's "red flag" could be another patient's reality.

"So many patients actually need to travel distances because there's no provider in their rural communities," Kurter said.

'Sometimes, that voice is a scream'

Wisconsin has more than 1,000 in-state, actively licensed pharmacies. The northern part of the state has fewer pharmacies; not all of them carry Suboxone.

Nine of the 14 patients the FOX6 Investigators spoke to said they have to drive 20 miles or more to their pharmacy; eight said at least once, a pharmacist has cited the distance as a reason to turn them away from filling their Suboxone prescription.

Others, like Kasten, say they've been turned away because the pharmacy did not have the medication available.

"If they have it, great," Kasten said. "If not, you're SOL."

The measures to prevent opioid abuse make it difficult to get the prescription quickly switched to a different pharmacy. Those same efforts are the reason patients receive just enough Suboxone to last until they can fill their next prescription; they get turned away if they attempt to refill too early.

As a result, Kasten says she has gone up to five days without her medication.

"It totally takes them off their tracks of recovery," Dr. Kurter said. "Because they're so focused on the withdrawal, and their physical pains of withdrawal, and the emotional pains of withdrawal, oftentimes, patients will likely relapse with the drug that they were offending in the first place."

"It's definitely not a, 'Oh shuckey, darn. Let's wait until next week or tomorrow,'" said Jaimie Hauch, licensed professional counselor. "It's usually 'I need this medication today.'"

Hauch works at West Grove Clinic and says the emotional impact of not being able to access treatment medication is just as important as the physical impact.

"Here, these people are trying to make positive changes, and then there’s a bump in the road that derails those positive changes," Hauch said.

"You have one day that you'll be OK because it's still in your system," Kasten said, describing what it feels like when she has to wait to get her Suboxone prescription filled. "But after that, I mean, you have sweats, headaches. You sneeze all the time. You're throwing up."

"There's that little voice since you don't have your safety net, that little voice like, 'Well, if you just do this, you'll feel better. You'll get your homework done. You'll get your kids taken care of,'" Kasten added. "And sometimes that voice is a scream."

Getting answers from pharmacies

Kurter says he supports efforts to prevent doctor shopping and pharmacy hopping, but he's concerned that inconsistencies will negatively affect his patients' treatment if they continue to have difficulty getting their medication.

"I think it's important for pharmacies to identify what their rules are and what their protocols are," Kurter said.

The FOX6 Investigators asked CVS, Walgreens, Walmart, Pick 'N Save, Costco, Aurora, Meijer, and Hayat pharmacies about their policies related to opioids, specifically dispensations for drugs like Suboxone.

A spokesperson for Aurora Health Care declined to answer questions, sending an email that said, "We do not have anybody available to participate at this time." FOX6 then asked if anyone could send information about Aurora pharmacy policies. No one responded.

Walmart, Pick 'N Save, Costco, and Meijer did not respond at all.

CVS sent links to its efforts surrounding "opioid utilization management," and put FOX6 in touch with a spokesperson with the National Association of Chain Drug Stores, which has advocated specific approaches for expanding access to medications used as part of addiction treatment.

A CVS spokesperson later clarified:

"As part of our pharmacists’ legally-required responsibilities under federal regulation regarding controlled substances, before filling a prescription for a controlled substance they may evaluate several factors to help determine whether the prescription was issued for a legitimate purpose. Unexplainable traveling or unreasonably long distances from a prescriber’s office could be among the factors a pharmacist evaluates."

Walgreens sent the following statement:

"Walgreens is committed to serving as part of the solution to opioid abuse and addiction. This includes our handling of highly complex issues that require collaboration among all stakeholders, including pharmacists and prescribers. Federal regulations require pharmacists to assess whether prescriptions for controlled substances, such as suboxone, are written for a legitimate medical purpose. While we do not have a specific policy that prohibits our pharmacists from filling controlled substance prescriptions for patients who have traveled more than 20 miles, the distance a patient has traveled can often be a warning sign, and is one of the factors our pharmacists take into account when exercising their professional judgment in connection with such prescriptions."

Dr. Hashim Zaibak, CEO of Hayat Pharmacy, is the only one who went on camera.

'Not as easy as black and white'

"We’re truly dealing with an epidemic," Zaibak said, describing the opioid issues his pharmacies deal with each day. "We are balancing between taking care of the patients and not helping with this epidemic."

Zaibak says he has spoken with several patients who experienced delays at other pharmacies when attempting to get Suboxone prescriptions filled; he says he has also talked to patients who were turned away because of the distance they traveled to get to their pharmacy.

"Unfortunately, it’s not as easy as black and white," Zaibak said. "A lot of times, you have to make a decision based on what you have, the information that you have."

While doctors want more consistency from pharmacies, pharmacists like Zaibak say the law leaves much to professional judgment on a case-by-case basis. Federal organizations, like the DEA, say that system is by design because smaller, local chains will naturally operate differently than the larger, national chains.

"The fact that we are local makes it easier for us to create our own policies within the general pharmacy law," Zaibak said. "We tell our pharmacists to use their best professional judgment."

Zaibak says one possible solution is the prescription naltrexone, known by the brand name Vivitrol. It is the only approved opioid treatment medication that is not a controlled substance. But Vivitrol is usually more expensive, sometimes by hundreds of dollars per month depending on insurance; doctors say it can also be harder to start because it usually requires abstinence from opioids and any other prescription medications for one to two weeks before beginning treatment.

Kasten says she isn't sure what the solution is, but wants the system to improve. She says focusing on recovery is already difficult without the "added roadblocks."

"It’s like, a touchy steering wheel, you know?" Kasten said. "You gotta drive real straight."