Opioid epidemic quadruples number of organ donors in WI: 'Their loved ones live on, but at a high price'

MILWAUKEE -- Losing a child can be devastating, but in tragedy, some are finding hope through new life.

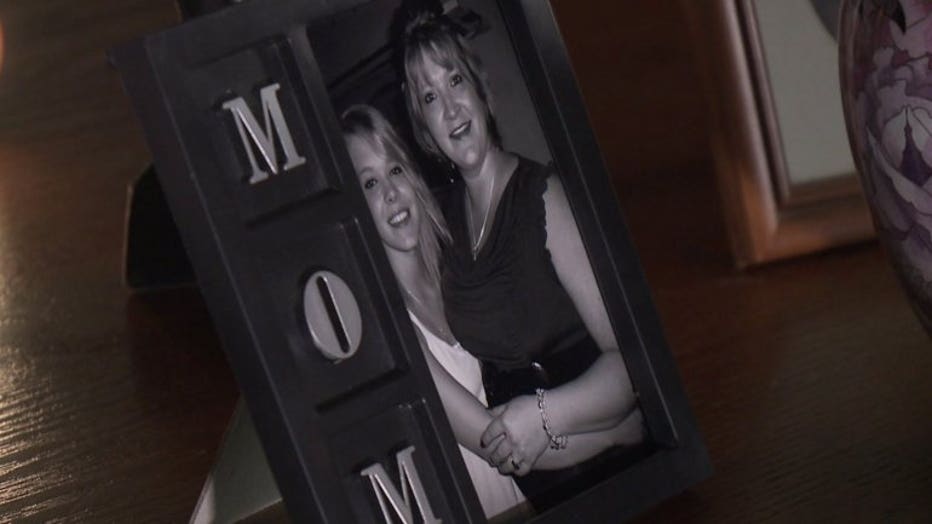

"She was a good kid. She had a really big heart. She was 17 -- very sassy, thought she knew everything. She was an excellent big sister," said Melanie Crandall.

Alexis Schoeffling

Crandall, of Jefferson, knows firsthand the unimaginable pain of losing a child. She said she often thinks about the "what ifs" six years after Alexis Schoeffling's death.

"Would I be a grandma? Where would she be working? Would I be yelling at her because she's still at home and not cleaning her bedroom?" said Crandall.

On Sept. 22, 2012, everything changed.

"As soon as I saw her, I knew that was it," said Crandall.

As she stared at her 17-year-old daughter in a hospital bed, her eyes closed, hooked up to machines, the dreams Crandall had for her little girl started to fade.

"That was my first thought -- that I'm never going to look into those eyes again," said Crandall.

Melanie Crandall

Schoeffling, once vibrant, lay dying. The high school senior had overdosed on heroin.

"I couldn't even fathom that she would do this. Like, why?" said Crandall.

Doctors at two hospitals tried saving her life, but there was nothing more they could do. She died two days after overdosing, and her mother was faced with the unthinkable.

"I was getting ready to plan for graduation and 'what are we going to do for the rest of your life,' conversation. Not, 'am I going to bury you' or 'am I going to cremate you?'" said Crandall.

In the midst of tragedy, there was a moment of clarity -- a decision that would allow her daughter to live on.

"She was still young and had so much of her life left. It's nice to be able to share that and pass that on," said Crandall.

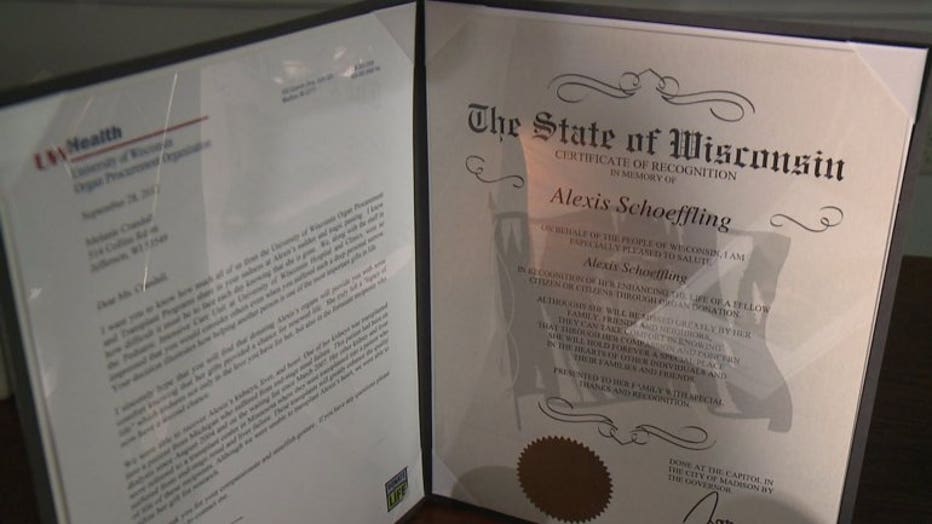

Schoeffling's heart was donated for research, a kidney given to a patient in Michigan, another kidney and liver given to someone in Minnesota. A dark moment became an opportunity to offer others the gift of life.

"She gave them a chance to be able to do stuff with their own, with their families. I think she would've liked that," said Crandall.

Dr. Ajay Sahajpal

Crandall's story is one more parents are sharing as the opioid epidemic continues to claim lives across the country. Overdoses are leading to bittersweet outcomes.

"As you have more and more young patients overdosing on opioids, we've noticed a correlation, an increase in the number of organs being transplanted across the country," said Dr. Ajay Sahajpal, director of abdominal transplant at Aurora Health Care.

According to the Organ Procurement and Transplant Network, the number of organ donors who have died from drug overdoses increased by more than 400 percent in the last decade -- a trend Dr. Sahajpal said is happening in Wisconsin as well.

"Since 2013, we've quadrupled the number of donors related to drug overdoses," said Sahajpal.

Oftentimes, donors are young and healthy. Rigorous testing is done to look for hepatitis and HIV. With more than 100,000 waiting for transplants, opioid overdoses have provided a flood of new donors.

"Families in their darkest hour can see something good come out of it and see a silver-lining, so their loved ones can live on, but it comes at a high price," said Sahajpal.

It's a price Crandall knows all too well. A letter and medal commemorate the gifts her 17-year-old daughter gave to two people.

"Parents that have lost a child struggle with making society see something positive out of that child," said Crandall.

Drugs may have taken her daughter's life, but they didn't destroy an opportunity to give others a future.

"I think she would be very happy with that," said Crandall.

Crandall now works with the group "Your Choice," teaching people about the dangers of heroin.